Crypto tax clarity in the U.S.: CoinTracker's 2025 crypto tax guide

Jan 31, 2025・30 min read

The crypto market's future may be unpredictable, and regulations are constantly evolving. But after surpassing a $3.5 trillion global market cap in 2024, one thing’s for sure: Cryptocurrencies are drawing more attention than ever from regulators and tax authorities worldwide. For U.S. citizens, that includes the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

To help you prepare your crypto taxes (and to take advantage of any potential deductions), here is CoinTracker's official crypto tax guide for the 2024 tax year.

Is crypto taxable? Do you have to pay taxes on crypto in the U.S.?

In many countries, investors must pay taxes on cryptocurrencies as they would for other forms of property. This is because any transaction involving selling, trading, or using crypto to buy goods or services usually triggers a taxable event. As a result, investors owe capital gains tax if they profit from their position after the sale.

Many nations also classify earnings from crypto-related activities like staking, yield farming, and mining as taxable income at the time they are received, based on their fair market value (FMV).

How is crypto taxed in the U.S.?

In 2014, the IRS issued Notice 2014-21 as its initial guidance on the taxation of cryptocurrencies. This notice established that, for tax purposes, virtual currency is treated as property, and therefore, the tax principles applicable to property transactions apply to virtual currency transactions. A few years later, in 2019, the IRS published its frequently asked questions (FAQs) on virtual currency transactions, which supplemented the initial guidance and have been updated multiple times. While the IRS has since moved away from the term “virtual currency,” the principles established in this guidance still remain applicable today.

The recently finalized Treasury and IRS regulations on digital asset reporting further refine cryptocurrency tax laws in the U.S. However, more regulations are still on the way, and some existing rules are under review or facing legal challenges. As the landscape continues to evolve, we’ll keep you updated on what you need to know.

The rules regarding how crypto is taxed in the U.S. are similar to those in many other countries. Because the IRS classifies digital assets as property, any profits earned after an investor sells or trades a position are subject to capital gains tax. The crypto tax rate usually depends on how long the investor holds the cryptocurrency and their marginal tax rate.

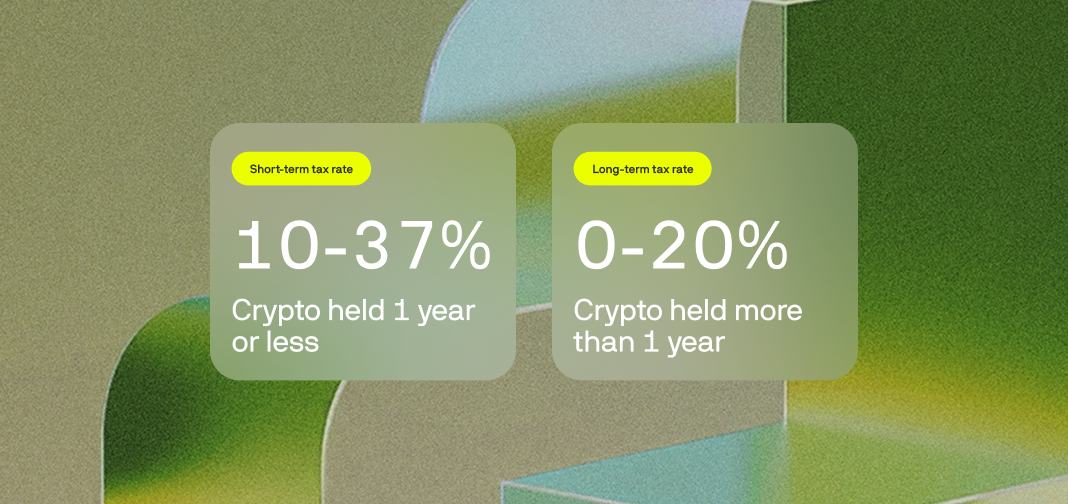

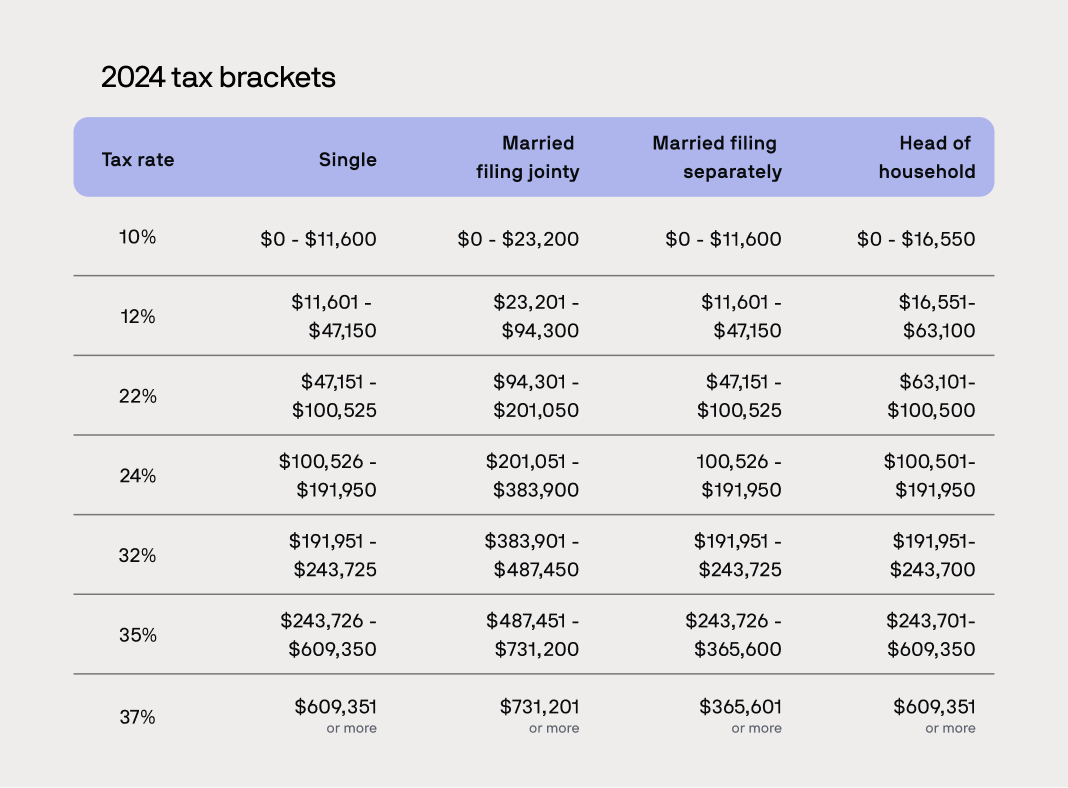

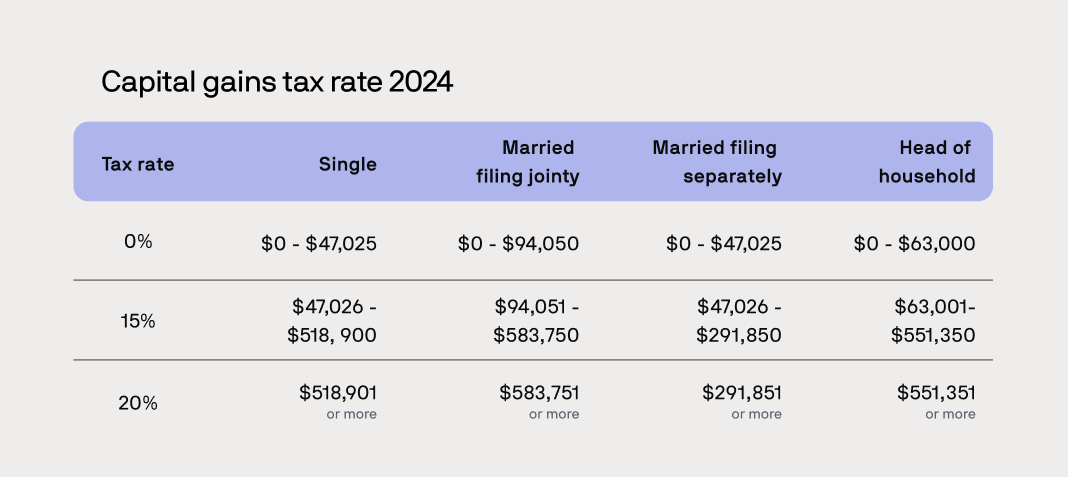

Selling crypto held for a year or less incurs short-term capital gains tax, aligned with the taxpayer’s ordinary income tax bracket. Crypto held for over a year qualifies for long-term capital gains tax, which offers preferential rates of 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on income level.

And like other nations, the U.S. also considers cryptocurrencies received through mining, staking rewards, hard forks, yield farming, liquidity provider tokens, or airdrops ordinary income (more on all those below). In these cases, taxes are based on the FMV of the digital assets at the time they are received.

When do you pay taxes on cryptocurrency?

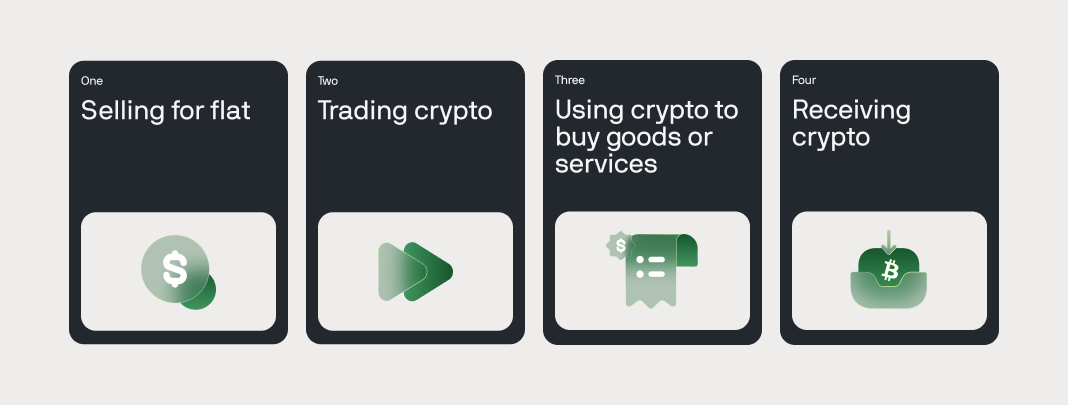

In general, there are four major taxable events you must include when filling out your tax forms:

- Selling cryptocurrency for a fiat currency (e.g., USD or EUR)

- Trading cryptocurrency for other digital assets

- Using cryptocurrency to buy goods or services

- Receiving cryptocurrency from a hard fork upgrade or passive income opportunities like mining, staking, or yield farming

Do you have to report crypto on taxes if you lose money?

Yes, whenever you sell, trade, exchange or use cryptocurrency to buy goods and services, the disposal must be reported whether you made or lost money. The good news is your losses might be beneficial because they may qualify for deductions to offset your capital gains.

If your capital losses exceed your capital gains, you can deduct up to $3,000 per year against ordinary income such as W-2 wages, business income or income from mining, staking, hard forks and airdrops and carry additional losses forward indefinitely to future years. CoinTracker’s Portfolio Tracker includes a tax-loss harvesting feature, making it easier for traders to strategically manage losses.

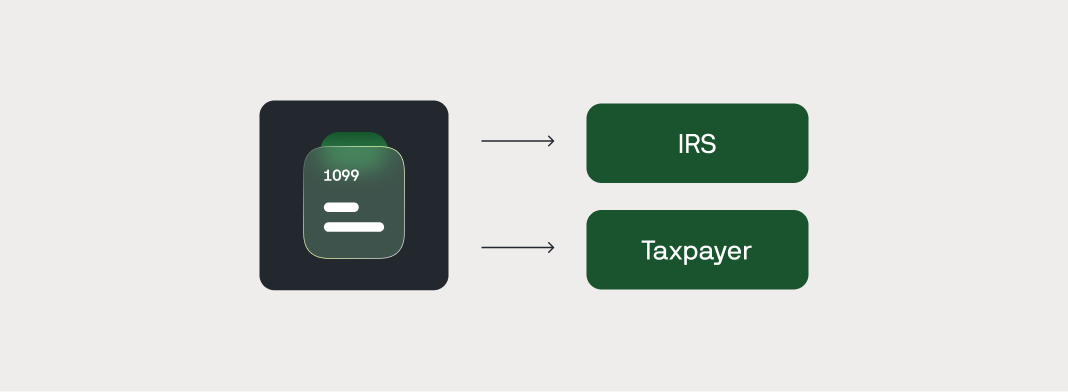

What happens if you don't report crypto taxes?

Failing to report crypto taxes can lead to audits, fines, and even jail time. The IRS has previously sent thousands of warning letters – such as 6173, 6174, and 6174-A – to crypto investors who didn’t report their taxes. Noncompliance can result in severe penalties, especially as the IRS increases its focus on digital assets. Remember that if your income is reported to you on a Form 1099, such as a 1099-MISC or the upcoming 1099-DA, the IRS will also receive a copy of this form, meaning that failure to report the income would lead to an automated notice. Even if your income or gains are not reported on a 1099, you must still report all of your income, as the IRS has other means for figuring out noncompliance, such as forensic tools and John Doe Summons.

Introduction to taxable events

Although cryptocurrencies are a taxable asset class, not all Web3 transactions result in tax liabilities. Only specific instances catch the IRS’s attention: taxable events.

What is a taxable event?

Taxable events refer to actions that create a tax liability. Any transaction involving the “disposal” of an asset for value – whether through a sale or exchange – typically qualifies as a taxable event. Taxpayers calculate their gains or losses from these disposals to determine their tax obligations. Receiving an asset as payment or a reward is also taxable but is treated as ordinary income rather than capital gains.

Common taxable events in crypto include selling digital assets for fiat or other cryptocurrencies, using crypto to pay for goods or services, or earning crypto as passive income.

Proceeds, cost basis, and fees explained

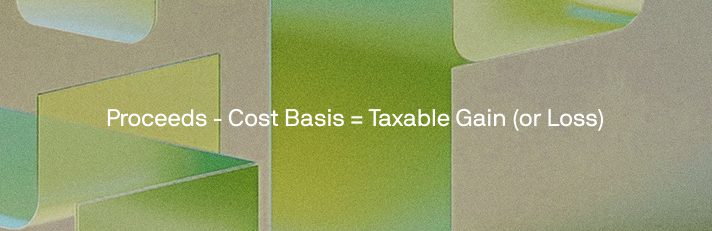

Internal Revenue Code §1001 establishes that the gain from the sale or other disposition of property is the excess of the amount realized (proceeds) over the adjusted basis (cost basis) of an asset, generally determined under §1012. Taxable income on capital gains follows this basic formula:

Proceeds refer to the total amount received from disposing of cryptocurrency, while the cost basis represents the average price paid to acquire the asset. Any extra fees you paid are also factored into this calculation, affecting the final taxable gain. For example, purchase fees add to the cost basis, while selling fees detract from the proceeds.

With crypto tax software like CoinTracker, incorporating these fees is not only easy – it also gives you a more accurate reflection of your actual cost per coin, which could potentially reduce your tax liability.

Example: Calculating taxable gains

Let’s say you purchase 0.5 Bitcoin (BTC) for $45,000 and pay $20 in purchase fees for the transaction. More than a year later, you sell your 0.5 BTC for $55,000, incurring $50 in selling fees. Following the formula to calculate capital gains, you would calculate your taxable gain as:

Proceeds: $55,000 proceeds - $50 selling fee = $54,950

Cost Basis: $45,000 purchase price + $20 purchase fee = $45,020

Taxable Gain: $54,950 - $45,020 = $9,930

Assuming you fall into a 15% crypto tax bracket, the capital gains tax owed to the IRS would be:

$9,930 x 15% = $1,489.50

Common taxable events

Selling crypto for cash is the most common example of a taxable event, but many other scenarios also require crypto investors to pay taxes. Even everyday activities, like using crypto to buy groceries, can trigger tax liabilities.

Selling cryptocurrency for fiat

When you cash out cryptocurrency for fiat currencies like USD, you owe taxes on any realized gains. The taxable amount is calculated as the difference between the sale price and the original purchase price, including any fees added to the cost basis. Depending on how long you held the cryptocurrency, the IRS categorizes the sale as either a short-term or long-term transaction. Your income bracket then determines the applicable tax rate for the resulting capital gain.

Trading cryptocurrency for other cryptocurrency

Exchanging one cryptocurrency for another, such as trading Bitcoin for Ethereum (ETH), is treated the same as selling for fiat. This is true even if exchanging one stablecoin for another, even if the gain or loss is negligible. Taxpayers calculate taxable gains using the FMV of the cryptocurrency received at the time of the trade compared to the cost basis of the cryptocurrency that was disposed of.

Using crypto on decentralized exchanges (DEXs)

Trading tokens on decentralized exchanges (DEXs) incurs capital gains taxes because it involves exchanging cryptocurrencies no different than trading on centralized exchanges (CEXs). However, the IRS taxes rewards earned by depositing digital assets into DEX liquidity pools as ordinary income, not capital gains.

Buying and selling NFTs

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) generally don’t have a 1:1 exchange rate like fungible cryptocurrencies, but they are taxable in certain situations, such as when they are sold or purchased.

Selling an NFT for crypto or fiat currency results in a taxable gain or loss, calculated based on the difference between the sale price and the NFT’s cost basis.

Purchasing an NFT with cryptocurrency is also a taxable event because it involves disposing of crypto. Similar to trading one cryptocurrency for another, the taxable amount equals the difference between the cryptocurrency’s cost basis and the NFT’s fiat value at the time of purchase, which also becomes the NFT’s cost basis.

Trading stablecoins

Stablecoins like Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC) mirror the value of their respective fiat currencies (in this case USD), but trading them for crypto, fiat, or other stablecoins is taxable. Every transaction that involves stablecoins could trigger capital gains or losses relative to your cost basis in these cryptocurrencies.

Any minor pricing fluctuations between a stablecoin’s cost basis and its fiat equivalent at the time of disposal could also trigger a taxable event.

Spending crypto on goods or services

Using cryptocurrency to pay for goods or services qualifies as a taxable event, similar to disposing of it for another asset. Taxpayers calculate the gain or loss as the difference between the fair market value of the goods or services received and the cryptocurrency’s cost basis. Simply put, imagine using crypto to pay for goods or services involves two separate transactions: first, trading it to fiat, and then using the fiat to buy the goods or services.

Short-term vs. long-term capital gains

The length of time you hold cryptocurrency (holding period) is a key factor in determining the tax percentage owed to the IRS from your profits. Generally, the longer you hold crypto, the lower your tax burden.

How holding periods affect tax rates

Crypto tax law divides gains into short-term and long-term categories. Gains from assets held for a year or less are taxed as short-term capital gains, while assets held for over a year qualify for long-term capital gain rates. Short-term rates are subject to your marginal income tax rate, while long-term gains are taxed at preferential rates.

Comparison of tax rates

Short-term capital gains are taxed at your income tax rate, ranging from 10% to 37%. Long-term capital gains are taxed at fixed rates of 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on your taxable income, which includes crypto gains and all other sources of income after deductions. For 0%, your annual income must be at or below $47,025 for single taxpayers or $94,050 for those married filing jointly. If your taxable income is between $47,026 and $518,900, you’ll pay 15%, while income above $518,900 is taxed at 20%. For married taxpayers filing jointly, if taxable income is between $94,051 and $583,750, you’ll pay 15%, while income above $583,750 is taxed at 20%.

Methods for calculating crypto gains and losses

Whether you use long-term strategies like dollar-cost averaging (DCA) or go the shorter route by trading crypto frequently, managing your portfolio's cost basis can get complicated. Frequent transactions, in particular, require careful tracking of purchase prices, sale prices, and fees to make sure you file accurately with the IRS.

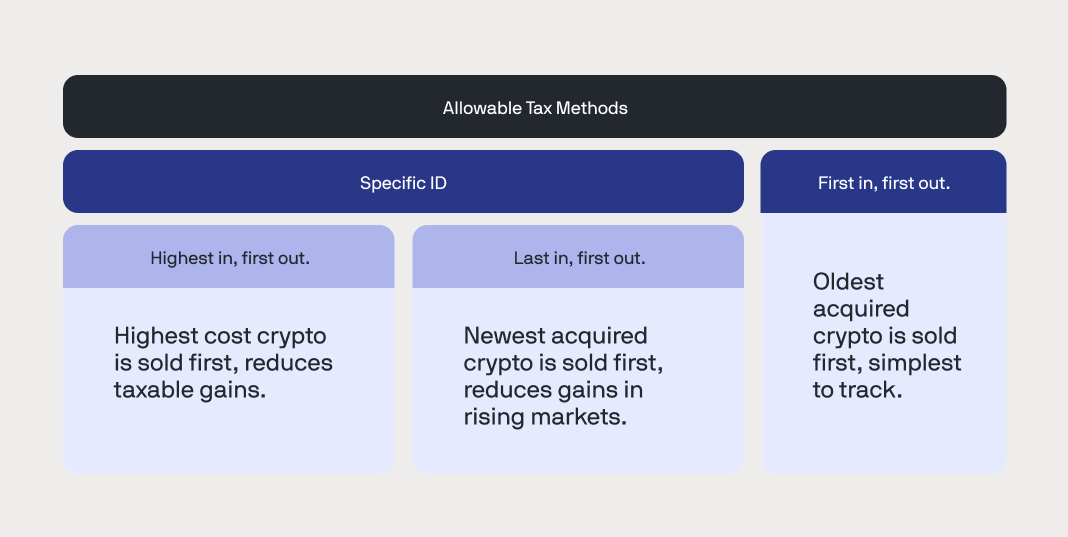

Currently, the IRS recognizes only Specific Identification (Spec-ID), including its subset methods, and “first-in, first-out” (FIFO) as valid crypto tax reporting methods.

Here's a closer look at these methods and how they work.

Accounting methods explained

Specific Identification (Spec-ID)

With Spec-ID, investors manually identify the specific crypto lots they sell to determine gains or losses. This method allows you to select which coins or tokens to dispose of, allowing greater control over your tax outcomes. Most exchanges will offer pre-configured options for Spec-ID, such as HIFO and LIFO.

LIFO

Short for "last-in, first-out," LIFO is the opposite of FIFO, assuming the most recently purchased cryptocurrency units are sold first. This method can be particularly advantageous in rising markets, increasing the cost basis per coin and potentially reducing taxable gains.

HIFO

HIFO ("highest-in, first-out") prioritizes selling the cryptocurrency units with the highest cost basis first, helping investors reduce their taxable gains. However, minimizing taxable gains doesn’t always reduce your tax liability. For example, using HIFO, you could sell higher-cost crypto in the short term, leading to a higher tax rate. In contrast, FIFO could result in higher taxable gains but qualify for the long-term capital gains tax rate, potentially lowering your overall tax liability.

Both LIFO and HIFO are specialized variations of the IRS-approved Specific Identification (Spec-ID) method and offer flexibility for minimizing taxable gains, provided that stringent documentation requirements are met.

Using LIFO and HIFO is allowed by the IRS, but just like with Spec-ID, you must select and document it as your preferred approach before selling, which requires meticulous record-keeping. Crypto tax software like CoinTracker simplifies the process by organizing and maintaining detailed records to help you make sure you comply with IRS regulations.

FIFO

FIFO is generally the default method for reporting unless you select a different method of accounting. This method assumes the first cryptocurrency units you purchase are the first ones you’ll sell. FIFO is relatively simple to calculate but may not be the most tax-efficient option, especially in rising markets where older, lower-cost coins are usually sold first.

FIFO, LIFO, and HIFO examples

Let's look at a few hypothetical examples to illustrate FIFO, LIFO, and HIFO and how they differ as cost basis calculations. For each, we'll use the same three purchases for Bitcoin arranged from oldest to newest:

- You purchase 1 BTC for $10,000

- You purchase 1 BTC for $25,000

- You purchase 1 BTC for $15,000

Now, let's assume you sell your 1 BTC for $100,000. Here's how the cost basis and taxable gain would differ depending on the method you choose:

- FIFO: Subtracting the oldest purchase price ($10,000), the taxable gain is $90,000 ($100,000 - $10,000).

- LIFO: Using the most recent purchase price ($15,000), the taxable gain is $85,000 ($100,000 - $15,000).

- HIFO: Subtracting the highest purchase price ($25,000), the taxable gain is $75,000 ($100,000 - $25,000).

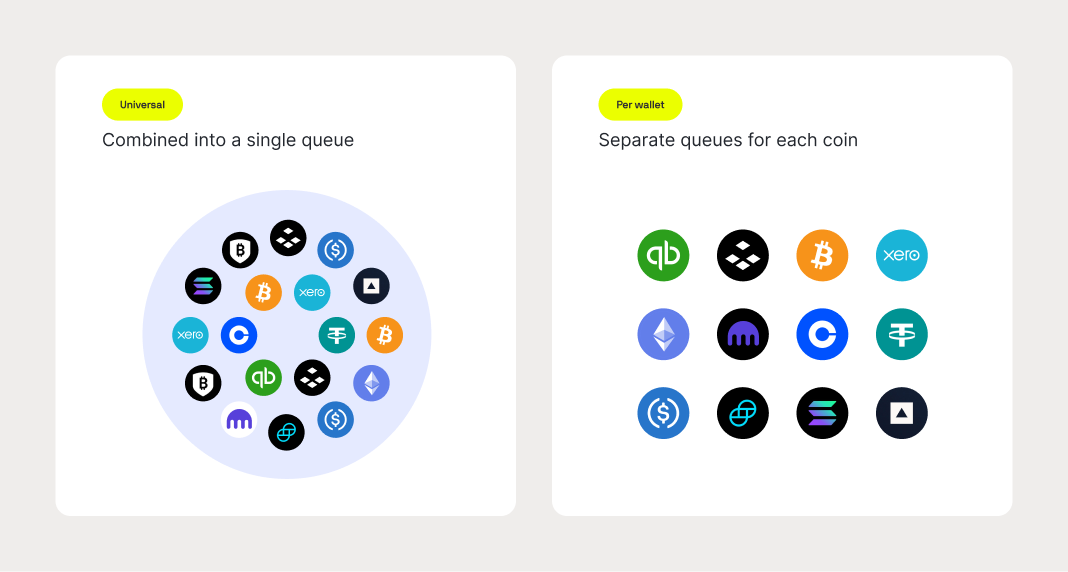

Universal vs. wallet-specific tracking

Many crypto investors use multiple wallets and accounts to manage their digital assets, which can be convenient for diversifying holdings or optimizing trades. But doing so can also potentially complicate cost basis calculations. Here’s why:

Originally, the IRS did not explicitly disallow the "universal tracking method," which treated all transactions for a cryptocurrency as part of a single pool. This allowed investors to calculate cost basis based on their selected tax method without tying it to the specific wallet or account where the assets were stored. Instead, the tax method was applied universally to the pool of all holdings of the same asset. For example, if each BTC in a portfolio was purchased on three different exchanges, the universal tracking method allowed taxpayers to apply their chosen tax method to dispose of the most optimal coin, regardless of the exchange from which the crypto was sold.

As part of the new crypto reporting regulations, which took effect on January 1, 2025, the IRS now mandates "per-wallet tracking." This requires investors to calculate the cost basis separately for each wallet or exchange, tying it directly to the specific assets in the account used for buying or selling crypto. For taxpayers who were previously reporting using the universal tracking method, the IRS issued Revenue Procedure 2024-28 (Rev. Proc. 2024-28) to help taxpayers transition from universal to per-wallet tracking.

Per-wallet tracking gives a more precise view of gains and losses, but it also adds another layer of complexity to your tax reporting. CoinTracker's Portfolio Tracker helps by organizing wallet-specific details and making it easier for you to transition from universal to per-wallet tracking while staying compliant with IRS standards (more on that below).

Transitioning to wallet-based accounting

To help ease the shift to mandatory per-wallet tracking, which took effect on January 1, 2025, the IRS introduced a safe harbor provision that allows traders who previously used universal tracking to extend their historical allocations without recalculations or audits. This means gains and losses from the previous universal method carry over into the new reporting system.

Under the new rules, investors are required to calculate gains and losses separately for each wallet or exchange. Consolidating individual digital assets into specific wallets or exchange accounts can simplify cost basis management and reduce tax complexity.

CoinTracker can help organize data for this transition, and consulting a crypto CPA can also offer valuable insights into how these changes impact portfolio management.

Evolving tax rules for other types of crypto transactions

One of crypto's defining traits is its constant evolution, which has led to innovations like wrapped tokens, liquidity pools, and on-chain derivatives. While tax authorities rush to keep pace with the rapid advancements in decentralized finance (DeFi), the technological breakthroughs that happen in the meantime often blur the lines regarding what you need to report to the IRS.

Wrapped tokens and their tax implications

Wrapped tokens are a special class of cryptocurrencies that represent a synthetic copy of another coin on a different blockchain. They enable one cryptocurrency to operate on an otherwise incompatible blockchain by mirroring the value of the original asset. For example, wrapped Bitcoin (wBTC) is a synthetic copy of Bitcoin that mirrors its price but functions on the Ethereum (ETH) blockchain. Wrapped tokens are often used when “bridging” assets, allowing them to move between blockchains.

Whether wrapping or unwrapping a token is a taxable exchange is currently not entirely clear. While you are, in fact, exchanging one token for another (e.g., BTC for WBTC), which suggests this should be a taxable exchange, an argument can be made that when wrapping or unwrapping an asset, the investor still holds the same economic position since these tokens mirror the underlying asset’s price.

In the recently issued Notice 2024-57, the IRS and Treasury acknowledged that they need more time to study certain transactions, such as wrapping and unwrapping transactions. Until then, such transactions are not reportable on the upcoming Form 1099-DA. This does not mean such transactions are non-taxable – investors are still responsible for determining the proper tax treatment and reporting accordingly.

The conservative approach is to treat wrapping and unwrapping transactions as taxable exchanges and report them as such. If you wish to take the aggressive approach, CoinTracker supports treating wrapping and unwrapping as non-taxable. We recommend going with the conservative approach for peace of mind. Regardless of your selected approach, you should be consistent in your reporting.

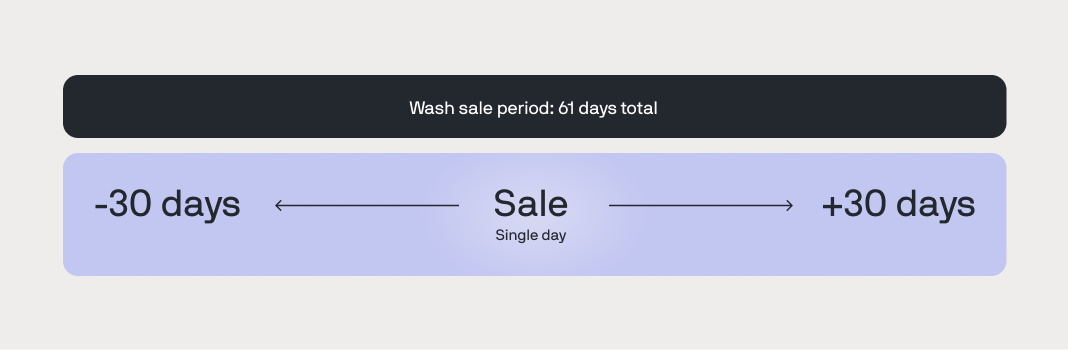

Wash sales

Wash selling occurs when an investor sells a stock or security at a loss and repurchases the same or a substantially identical security within 30 days as defined by §1091. For securities like stocks, bonds, and mutual funds, the loss gets deferred and added to the basis of the repurchased securities.

Cryptocurrencies, however, don’t typically qualify as stocks or securities, which creates a gray area for wash sales (at the time of writing). This means that if you sell a cryptocurrency at a loss and then repurchase within 30 days, you do not have to worry about wash sales and can claim the loss. Regardless, we do not recommend abusing this loophole, as the IRS could use the substance over form doctrine, which allows the agency to recharacterize transactions based on their economic reality rather than their structure. If the IRS determines that a transaction was structured solely to evade taxes rather than for a legitimate purpose, it may disallow the loss.

Again, crypto tax laws are constantly evolving. Congress may eventually extend the wash sale rule to cryptocurrencies, requiring traders to observe the 30-day limit when rebuying crypto after a loss.

Margin trading

Margin trading allows investors to borrow funds to increase their buying power when trading cryptocurrencies. This leverage amplifies potential gains but also increases the risk of losses. If the market moves unfavorably, traders may face liquidation, where their collateral is sold to cover losses.

The IRS has not provided explicit guidance on crypto margin trading taxation. However, margin trading gains and losses are generally treated as capital gains based on the closed profit and loss (P&L), similar to equities. If a position is liquidated, it is considered a taxable event, meaning the trader may owe taxes even if they didn’t voluntarily sell the asset.

Derivatives (futures, options, perpetuals)

Crypto derivatives are financial contracts that derive their value from the cryptocurrency on which the contracts are based, such as BTC, ETH, or SOL. Traders use them to speculate on price movements, hedge risk, gain exposure to assets without direct ownership, or to amplify return potential by using leverage. The three most common types of crypto derivatives are futures, options, and perpetual contracts.

- Crypto futures contracts are agreements to buy or sell an asset at a predetermined price on a specific future date.

- Crypto options contracts give traders the right (but not the obligation) to buy (call option) or sell (put option) an asset at a predetermined price.

- Perpetual contracts, unlike traditional futures, do not have an expiration date. Instead, they use funding rates to maintain price alignment with the spot market.

The tax treatment of crypto derivatives depends on whether they qualify as regulated or unregulated contracts. A regulated futures contract is one that is traded on a qualified exchange and follows mark-to-market rules, where required deposits and withdrawals adjust based on market fluctuations.

Those that qualify as regulated futures contracts under §1256, such as Bitcoin futures traded on CME Group, are subject to a special 60/40 rule:

- 60% of gains are considered long-term capital gains.

- 40% of gains are considered short-term capital gains.

- All open positions are marked-to-market at year-end, treated as if they were sold at FMV on the last business day of the tax year.

- These are reported on Form 6781.

Most crypto derivatives traded on crypto exchanges, whether CEXs or DEXs, are considered unregulated contracts and do not qualify for §1256 treatment. These are taxed under standard capital gains rules based on the closed P&L as either short-term or long-term gains (or losses) depending on the holding period.

Liquidations

A liquidation occurs when an exchange forcibly closes a trader’s position due to insufficient collateral. This typically happens in margin trading and leveraged derivatives positions.

Liquidations are treated as taxable disposals, resulting in capital gains or losses based on the asset’s fair market value at the time of liquidation.

Straddles

A straddle involves holding offsetting positions in the same or substantially identical property, such as a long and short position simultaneously. This strategy is commonly used to hedge risks. Straddle rules were enacted to prevent income deferral and the conversion of short-term gains into long-term gains.

Under §1092, straddle rules apply to offsetting positions in personal property, which includes assets like stocks, bonds, and other instruments actively traded on established financial markets. Losses from one position in a straddle are deferred to the extent of unrealized gains in the offsetting position, and the holding period for straddle positions is suspended.

For cryptocurrency investors, the application of straddle rules remains uncertain, as the IRS has not provided specific guidance. Taxpayers with multiple crypto positions should carefully assess whether their holdings reduce risk in a way that could trigger these rules. As tax regulations evolve, ongoing analysis of portfolios for potential straddle treatment is crucial.

Shorting

Another strategy that involves unique tax considerations is short selling (or shorting). This approach occurs when an investor sells borrowed property, such as cryptocurrency, intending to repurchase it later at a lower price. In most cases, gains or losses from shorting crypto are based on the closed P&L.

Shorting presents distinct tax challenges because the timing and treatment of the gain or loss depend on the property’s classification as a capital asset. Under §1233(a), gain or loss from a short sale is treated as capital gain or loss if the property used to close the sale is a capital asset. However, special short sale rules under §1233(b) and §1233(d) may apply if the taxpayer holds or acquires substantially identical property at the time of the sale. These rules can override the holding period of the property used to close the short sale and recharacterize the gain or loss as short-term or long-term, depending on the circumstances.

It’s also worth noting that many cryptocurrencies may fall outside the scope of the special short sale rules under §1233(e), as these rules are limited to certain types of property, such as stocks, securities, and commodity futures. However, futures contracts on digital assets like BTC or ETH may qualify.

Constructive sales under §1259 may require a taxpayer to recognize gain as if an appreciated financial position were sold, even without an actual sale. This can occur when an investor enters certain offsetting transactions, such as a short sale, futures, or forward contract, involving the same or substantially identical property. However, these rules generally do not apply to cryptocurrency, as they are not considered stock, debt instruments, or partnership interests.

Again, if you’re considering or already using these types of advanced strategies, maintaining detailed logs of all your activities is vital to minimizing the risk of audits or penalties.

Reporting losses, scams, and theft

Hacks, exchange bankruptcies, and pump-and-dump schemes are a few of the currently – and unfortunately too common – issues in the crypto space. While cryptocurrencies aren’t federally backed or insured, there are ways to potentially recover losses when you file your income tax return.

Reporting losses from bankrupt exchanges

Reclaiming losses from bankrupt crypto exchanges like FTX, Mt.Gox, or Voyager depends on each company’s current legal proceedings. From a tax standpoint, it’s possible to claim certain losses such as abandonment, casualty, or Ponzi losses, on assets held in a bankrupt exchange. If the exchange issued a now-worthless proprietary cryptocurrency (e.g., FTX’s FTT token), these losses may also be deductible.

If you received any crypto from an exchange that later froze withdrawals or declared bankruptcy, you are still required to report that income for the year it was credited to your account. This was confirmed by the IRS, explaining that income is recognized when it is credited and under the taxpayer’s control, even if access is later restricted.

Strategies for claiming loss deductions

To claim losses successfully, keep detailed records like transaction histories and account statements with timestamps. Stay informed about bankruptcy proceedings and organize any related communications to ensure accurate reporting. When reporting a loss, you will generally use the cost basis of the lost cryptocurrency but must consider any recoveries.

If the bankruptcy is linked to fraud, such as a Ponzi scheme, losses might qualify as theft under Rev. Proc. 2009-20, which could allow deductions based on the value of lost assets minus any potential recoveries.

Reporting losses from bankrupt exchanges can be highly complex as investors must consider all facts and circumstances while there is limited guidance from the IRS. Even bankruptcy payments, such as those from Celsius, come with many considerations. Due to these complexities, we recommend individuals consult with a tax professional to properly evaluate their situation and options for reporting.

Taxable income from crypto activities

The IRS typically classifies cryptocurrencies received as rewards or payments as ordinary income. However, once these digital assets are acquired, their tax treatment transitions to capital gains when they’re sold or exchanged. The initial guidance on income came when the IRS answered that mined cryptocurrency is considered gross income in Notice 2014-21, and later when it issued Revenue Ruling 2019-24 stating that hard forks and airdrops were also taxable income if taxpayers received additional tokens.

Income for investors

Investors can earn cryptocurrency in various ways, such as through mining rigs or receiving complementary assets via airdrops or hard fork upgrades. In these cases, the IRS considers the rewards as ordinary income, requiring reporting under “other income” based on the FMV at the time of receipt. The FMV at receipt also becomes the cost basis for calculating capital gains or losses when the assets are sold.

The types of income that are subject to this reporting include, but are not limited to:

- Mining or block rewards

- Staking rewards

- Masternodes rewards

- Hard forks

- Airdrops

- Liquidity pool rewards

- Any form of interest or yield

- Any other rewards (such as learning rewards offered by certain exchanges)

Simply put, if you open your wallet or account and you have additional coins or tokens that you did not purchase or trade for, it is likely ordinary income.

If you earn $600 or more of income or rewards through a centralized exchange, they will likely issue a Form 1099-MISC to report your income. As with any other 1099 received, a copy is filed with the IRS so it is critical you report accordingly on your individual income tax return. The amount reported in box 3, other income, will be the USD equivalent of the FMV of all income earned through the exchange. If you earn under $600 and/or if you earn any amount of income on decentralized applications, you will not receive a 1099-MISC. Keep in mind that even if you do not receive a form, you should report all income from such activities to avoid any issues with the IRS.

Income for businesses

Trades or businesses accepting cryptocurrency as payment must report it as gross income based on the FMV of the crypto at the time of the transaction. They can deduct business expenses like wages, repairs, depreciation, crypto payment processor fees, and any other ordinary and necessary expenses. To calculate taxable income, subtract allowable deductions from gross income.

Income for contractors or employees

Contractors and employees receiving cryptocurrency for work must report it as ordinary income on their individual income tax return. This income will be reported to you on forms like 1099-NEC or W-2. The USD equivalent of the FMV of the cryptocurrency at the time of receipt will be reported in box 1 (of both forms), so you do not have to worry about calculating the value for this purpose. Despite that, you should track your cryptocurrency once received with software like CoinTracker, as it will be subject to capital gains tax when you sell or trade your crypto, with the FMV reported as income also serving as the cost basis.

Tax-exempt and non-taxable crypto transactions

Not every move you make in the cryptocurrency realm results in a tax liability. There are many instances when a transaction will not trigger a taxable event and will not have to be reported. Regardless, you should make sure to properly track as the cost basis and holding period of the assets will always be impacted.

What crypto transactions are tax-exempt?

Buying cryptocurrency with fiat

Purchasing crypto using fiat currencies on exchanges, ATMs, or peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms doesn’t trigger tax implications. Taxes only apply when cryptocurrencies are sold or used.

Transferring crypto between wallets

Moving crypto between wallets or exchanges under the same investor’s control is non-taxable. You should track both sides of the transfer properly for your records. CoinTracker will automatically detect your transfers once your wallets are connected.

Holding cryptocurrency (HODLing)

The long-term strategy of holding cryptocurrency, or "HODLing," doesn’t incur taxes as long as the assets remain in a wallet (or multiple wallets) and aren’t used for passive income activities like staking. If you do earn any income for HODLing, refer to Income for investors.

Tax rules for crypto gifts

Sending cryptocurrency as a gift is not subject to income tax, regardless of the amount. However, if the gift exceeds the IRS’s annual gift threshold of $18,000 or $36,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly (for the 2024 tax year – for 2025, those amounts will increase to $19,000 and $38,000, respectively), the donor may be required to file a gift tax return. While reporting may be required, gift tax is generally not owed unless the donor exceeds their lifetime exemption, currently $13.61M.

The recipient’s cost basis is the donor’s original basis if the cryptocurrency’s FMV at the time of the gift is equal to or greater than the donor’s basis. If the FMV at the time of the gift is lower than the donor’s adjusted basis, the recipient’s cost basis depends on whether there is a gain or loss when disposing of the crypto.

When determining a gain, the recipient generally uses the donor’s adjusted basis. For a loss, the recipient uses the cryptocurrency’s FMV at the time of the gift. If using the donor’s basis for determining a gain results in a loss, the sale is treated as having no tax effect.

Charitable donations in crypto

Donating cryptocurrency to a qualified 501(c)(3) charity may qualify for a tax deduction while avoiding recognition of gain or loss on the disposal. If you hold crypto for more than a year, you can deduct the donation’s FMV from your taxable income if you itemize deductions. For crypto you’ve held for a year or less, you can typically deduct the lower of your cost basis or FMV.

Contributions to charitable organizations are generally deductible up to 50% of adjusted gross income (AGI), while donations to certain private foundations, veterans organizations, fraternal societies, and cemetery organizations are limited to 30% of AGI. Investors can use the Tax Exempt Organization Search to find the proper limitation for an organization.

DeFi taxation

If you’re interested in – or already using – DeFi to explore trading opportunities or earn passive income, it's important to understand how the IRS’s tax rules apply. Here’s a quick breakdown to help you navigate potential impacts on your earnings.

What is DeFi?

DeFi uses blockchain-based decentralized applications (dApps) to offer financial services – like trading and asset management – without relying on banks or financial institutions. By operating on public blockchains, DeFi enables peer-to-peer (P2P) transactions and asset tokenization and also supports stablecoin utilization and strategies like yield farming, all without intermediaries.

Bitcoin paved the way for peer-to-peer (P2P) trading, but the introduction of smart contracts on platforms like Ethereum (ETH) sparked explosive growth in DeFi. While Ethereum remains a go-to hub for DeFi activity, blockchains like Binance Smart Chain and Solana are expanding their reach with increasingly advanced smart contract ecosystems.

DEX taxation

DEXs are decentralized, but they’re not exempt from the standard taxes applied to centralized exchanges (CEXs). Investors trading cryptocurrencies on DEXs must report capital gains or losses for these transactions, which are calculated the same as transactions on CEXs – that is, by subtracting the token’s cost basis from the proceeds received.

For investors providing liquidity to DEXs, acquiring or disposing of liquidity provider tokens (LP tokens) should generally be treated as a taxable disposal since you're exchanging different assets (e.g., ETH and USDC for ETH/USDC LP tokens).

Just as with wrapping transactions, in the recently issued Notice 2024-57, the IRS and Treasury acknowledged that they need more time to study liquidity pool transactions. This does not mean that such transactions are not taxable, and investors should carefully assess the risks of taking the aggressive position that liquidity pool transactions are non-taxable.

For those who want to take this calculated risk, CoinTracker does support treating such transactions as non-taxable. Regardless of how you report adding or removing liquidity, any rewards from digital assets deposited into liquidity pools must be reported annually as ordinary income.

Lending and borrowing taxation

Another passive income option in DeFi is loaning cryptocurrency through dApps like Aave (AAVE) or Compound (COMP) to earn interest. Many lending dApps use crypto-to-crypto swaps to facilitate the loans. For example, an investor lending ETH through Aave will receive aETH tokens in exchange for their ETH. Similarly, supplying ETH on Compound would result in the investor receiving cETH in exchange.

While the IRS has not issued specific guidance on these transactions, these tokens have value on their own and can be traded on other DEXs, such as Uniswap, for other tokens. This means that the initial supply of ETH (or any other asset) for aTokens or cTokens more closely resembles a taxable exchange rather than a loan. As such, we recommend taking the conservative approach and treating these transactions as taxable exchanges. For investors working with a tax professional who want to take a more aggressive stance, CoinTracker supports treating these transactions as non-taxable.

As with liquidity pool transactions, regardless of how you report the loan, investors must report any interest earned as ordinary income for tax purposes. However, due to data limitations, it may be necessary to only report the taxable exchanges with any earned rewards factored into the selling price.

For those who fail to meet the loan-to-value ratio and get liquidated, the liquidations could lead to capital gains if the liquidation price is higher than your cost basis.

Staking taxation

Staking involves locking cryptocurrency on a proof-of-stake protocol, such as ETH or SOL, by validating transactions and securing the network in exchange for staking rewards. There are two main forms of staking, illiquid staking and liquid staking.

Illiquid staking is the traditional form of staking where your assets are locked into a smart contract, and you do not receive any other tokens in return. It resembles making a deposit into an interest-bearing account. The initial deposit of the assets into the smart contract is not a taxable event, but any rewards received are generally considered taxable ordinary income based on the FMV of the rewards at the time of receipt. Upon disposal, this FMV becomes the cost basis for figuring out your gain or loss. The IRS issued Rev. Rul. 2023-14, taking this stance, stating that staking should be included in income at the time of receipt. Despite this, some investors still treat staking as taxable only upon sale, recognizing no income upon receipt and taking a zero-cost basis. Given the IRS’s guidance, this is an aggressive stance, but for those working with a tax professional who feel comfortable with this, CoinTracker allows you to treat staking rewards as taxable only upon disposal.

By contrast, with liquid staking, investors receive synthetic tokens for their staked assets, such as stETH. These tokens can be traded on other DEXs, so the transaction more closely resembles a taxable exchange. In these cases, the staking and unstaking transactions are both taxable disposals subject to capital gains taxes, as you're exchanging one asset for another.

Yield farming

Yield farming is a competitive DeFi practice where traders seek the highest returns by lending, staking and/or providing liquidity across multiple dApps. These activities are generally taxable, the same as each individual activity (lending, staking, liquidity).

Gas fees

Gas fees are transaction costs paid to blockchain validators for validating transactions and are a standard expense in DeFi. While blockchains like Solana (SOL) and Arbitrum (ARB) are known for low fees, Ethereum often incurs higher fees during network congestion. Gas fees directly tied to buying or selling cryptocurrencies in DeFi may be deductible from capital gains. For those using cryptocurrency in a business context, gas fees might also qualify as deductible business expenses.

Investors who frequently use DeFi – or operate on high-fee chains like Ethereum – should pay special attention to these fees. Regardless of magnitude, you should include gas fees in your crypto tax reports.

NFT taxation

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) became highly popular during the 2020–2021 bull market. Despite their unique nature and unpredictable pricing, there are many taxable events an investor must consider when buying and selling NFTs.

About NFTs

NFTs share several traits with other cryptocurrencies, like decentralization and peer-to-peer transferability, but each NFT has unique metadata. Whether representing an image, audio file, or video game item, this non-duplicable data means it’s impossible for any NFT to have a 1:1 market value on standard crypto exchanges. Instead, they trade on platforms like OpenSea or Magic Eden, where prices are set case by case.

NFT taxation

Like other cryptocurrencies, the IRS considers NFTs property, which means they're subject to capital gains or losses based on the difference between the cost basis of the NFT and sale price. Purchasing an NFT with cryptocurrency is also a taxable event. If you use a coin like Wrapped Ethereum (wETH), Solana, or USDC to purchase an NFT, you must account for any gains or losses from disposing of the cryptocurrency relative to the NFT's FMV at purchase.

Minting NFTs

When a new NFT collection launches, collectors and investors can mint a unique NFT by paying a fee. On platforms like Magic Eden, for example, this process involves paying a fee and receiving a brand new, unique NFT from the collection in exchange for the fee. Minting fees are added to the NFT’s cost basis, and purchasing the NFT is treated as a taxable disposal if cryptocurrency is used, similar to trading crypto for an NFT.

NFT income

Certain NFTs also offer investors the opportunity to earn passive income through staking and airdrops. Like other cryptocurrencies, some NFTs can be "staked" in exchange for rewards, such as new tokens. In addition, holding certain NFTs also earns the holders the right to receive airdrops from new collections. Whether you're receiving staking rewards or airdrops of new NFTs (or fungible tokens), both events are taxable and considered ordinary income based on the FMV of the NFT or tokens received. Be careful of spam NFTs that have no value and are often disguised scams attempting to make you take certain actions that could drain your wallet.

NFT creators

Creators selling NFTs must report any sales as taxable income. Royalties earned from any future resales are also taxable. For those creating NFTs as part of a trade or business, such as operating a digital studio or building a brand around NFT-based content, any ordinary and necessary business-related expenses, such as software, marketing, design costs, or transaction fees, may be deductible from the gross sales to determine the taxable income from the activity. This should be reported on the proper business tax form or schedule, such as Form 1065 or Schedule C.

DAO taxation

Decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) aim to make blockchain decision-making more democratic. DAOs allow members to vote on proposals using special cryptocurrencies called governance tokens. While voting might not seem taxable, some platforms that run DAOs reward participants with additional tokens, which are considered taxable as income when earned and subject to capital gains taxes when sold.

Capital gains for token holders

If you're an investor who sells DAO tokens, you must report the difference between the sale price and the original purchase price (cost basis) as capital gains or losses. Rewards earned in governance tokens through activities like airdrops or staking are considered ordinary income for tax purposes. Using DAO tokens for voting doesn't usually trigger a taxable event, but gas fees related to voting can result in a taxable disposal and generate a gain or loss.

DAO taxation itself as a business

There’s no definitive IRS guidance yet on whether DAOs should be treated as business entities for tax purposes. Depending on their structure and operations, DAOs could be classified as partnerships, where income is passed on to the owners and taxed individually, or as corporations subject to corporate tax rules.

Despite these uncertainties, DAO members must report income from token issuance and profits from selling governance tokens as capital gains. The exact tax treatment of the DAO’s income depends on the DAO’s structure, how income is distributed, and applicable tax regulations.

Crypto taxes in 2025: Simple and secure with CoinTracker

Whether you're filing for fiat or crypto this tax season, you should never count on the IRS to miss a beat. But you can count on CoinTracker—named one of the World’s Top Fintech Companies 2025 by CNBC & Statista—to make the process effortless.

CoinTracker syncs with 500+ exchanges and wallets, 10,000+ cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and 20,000+ DeFi smart contracts – all while staying on top of your gains and losses. Join the millions of users who trust CoinTracker for accurate, compliant crypto tax reports year-round. Generate tax-compliant reports in minutes that are ready to share with your CPA or import them directly into TurboTax and H&R Block.

Disclaimer: This post is informational only and is not intended as tax advice. For tax advice, please consult a tax professional.